6. Basic Unix : shell variables¶

Setting and applying shell variables

Use of variables is essential in writing processing scripts, allowing the scripts to be easily modified for use with different subjects, data inputs or processing control parameters (blur size, censor limit, etc).

Shell variables allow one to change a single variable assignment, rather than the 50 places where it is used, for example.

Commands and descriptions:

6.1. Setting and accessing a variable¶

Define a variable ‘subj’ to be a subject identification code. Perhaps all of our subjects have codes starting with ‘s’, followed by 3 digits.

commands (type these in the terminal window):

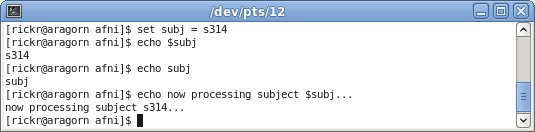

set subj = s314 echo $subj echo subj echo now processing subject $subj...

The first line has no output, it simply creates a variable ‘subj’ with value ‘s314’. The subsequent echo command shows use of ‘$’ to access the value of a variable. A ‘$’ followed by (adjacent) text means to replace the variable with its value before executing the command.

The

echo subjcommand has no ‘$’ before subj, so ‘subj’ is treated as simple text, not a variable. The third echo command shows accessing $subj in a common way: informing the user of a script what is happening.

6.2. Delete the variable and try again¶

What happens when one tries to access an unset (non-existent) variable?

commands (type these in the terminal window):

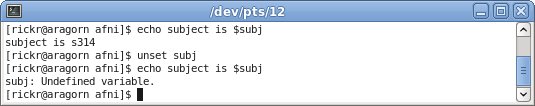

echo subject is $subj unset subj echo subject is $subj

The first command just confirms the current value of subj, still showing s314. The ‘unset’ command destroys the variable, so it no longer exists.

Consequently, the final echo $subj command results in a shell error:

subj: Undefined variable.

This particular error message is very clear: the shell does not know of any variable named ‘subj’. So an “Undefined variable” error means that the given variable has not been set (maybe a typo, maybe a logic error).

See also

6.3. Set a variable to some directory¶

There is nothing special about assigning a directory name to a

variable, except that it could then be used in cd or ls

commands.

commands (type these in the terminal window):

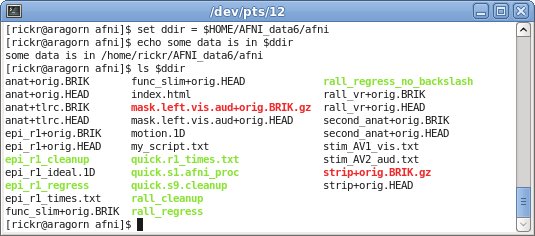

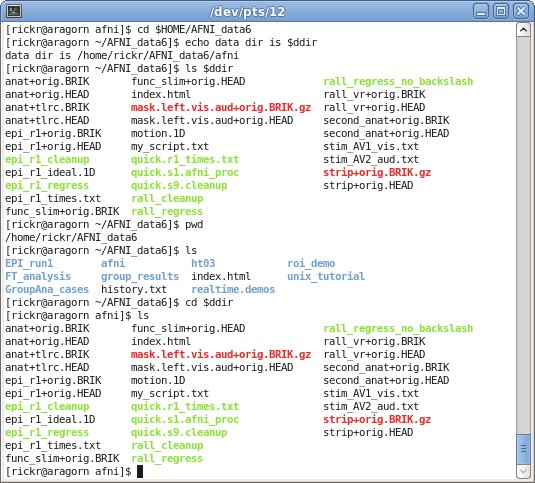

set ddir = $HOME/AFNI_data6/afni echo some data is in $ddir ls $ddir

Here ‘ddir’ is defined to be the name of our main sample directory. The ‘echo’ command simply confirms the new variable’s value, which is still just some text, but happens to be the name of a directory.

The

lscommand shows the contents of that directory. The shell expands$ddirbefore thelscommand is envoked.

6.4. Maybe we made a mistake¶

There are, of course, many ways to make mistakes. But consider an example where we just specify the wrong name of the directory.

commands (type these in the terminal window):

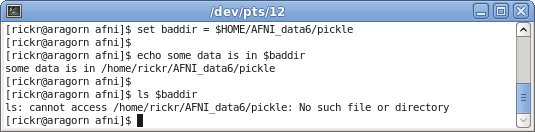

set baddir = $HOME/AFNI_data6/pickle echo some data is in $baddir ls $baddir

The commands are almost identical to those above, except:

we used a new variable name,

baddirinstead ofddirwe specified AFNI_data6/pickle instead of AFNI_data6/afni

The first two commands work just like before. But the third command fails because we “accidentally” typed ‘pickle’ instead of afni. Instead of a directory listing, we see:

ls: … : No such file or directory

6.5. Play with the $ddir variable¶

Use the current $ddir variable with some more commands.

Start in the AFNI_data6 directory.

commands (type these in the terminal window):

cd $HOME/AFNI_data6 echo data dir is $ddir ls $ddir pwd ls cd $ddir ls

The first 2 commands should be clear.

Though we start by going to a directory other than what

$ddirrefers to, since $ddir points to an existing class data directory, the ‘ls’ command should show its contents, regardless of where we are sitting.The ‘pwd’ command should confirm that we are in

AFNI_data6(though it does not really matter), as should the ‘ls’ command, in showing the contents of the current directory.Then

cd $ddirtakes us to that data directory, and the subsequentlscommand shows the same output as the initialls $ddircommand: the contents of the AFNI_data6/afni directory.Remember, if you see “No such file or directory”, then perhaps there is a typo in the $ddir value. If so, use the set command to set it to the correct directory name.

6.6. Valid variable names and {}¶

Variable names must start with an alphabetic letter (a-z,A-Z), and can then contain alphabetic letters, digits (0-9) and underscores (_).

valid: subj Var12345 subject_ID invalid: 123subj vv.T+id

commands (type these in the terminal window):

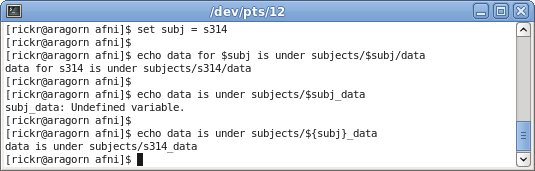

set subj = s314 echo data for $subj is under subjects/$subj/data echo data is under subjects/$subj_data echo data is under subjects/${subj}_data

After setting ‘subj’, the first echo statement should work fine.

However the second echo statement should produce an error. The shell sees

$subj_dataas a variable, and tries to return its value, but only$subjis defined, not$subj_data. This results in the error:subj_data: Undefined variable.

So ‘subj’ will have to be separated from ‘_data’, allowing it to be evaluated on its own.

That leads to the third echo command, where ‘subj’ is put within ‘{}’. The {} characters merely separate ‘subj’ from ‘_data’.

See also

6.7. Variables as part of dataset names¶

A subject ID variable will often be used as parts of input and output file names, as well as directory names, helping with data organization.

The only special thing here is a deviation from Unix-land to AFNI-land. Datasets do not need the .HEAD or .BRIK extension to be seen by AFNI programs, but to be seen by the shell or other Unix programs, they do.

commands (type these in the terminal window):

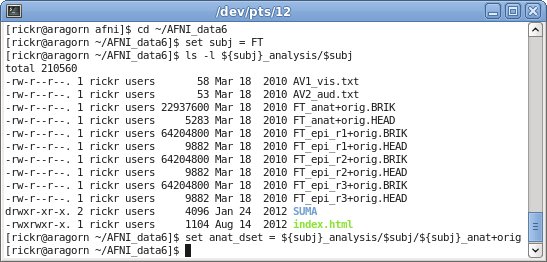

cd ~/AFNI_data6 set subj = FT ls -l ${subj}_analysis/$subj set anat_dset = ${subj}_analysis/$subj/${subj}_anat+orig

We start from AFNI_data6 for convenience, and set a subject ID variable to FT. Then we get a listing of the contents of that subject’s data directory. Including in that listing is the anatomical dataset FT_anat+orig (both the .BRIK and .HEAD files are used to make up the dataset).

So anat_dset is set to the name of that AFNI dataset, including the dataset prefix and view, but not the file extension.

Then …

commands (type these in the terminal window):

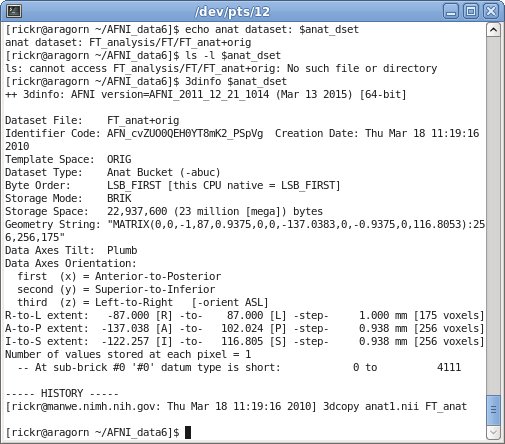

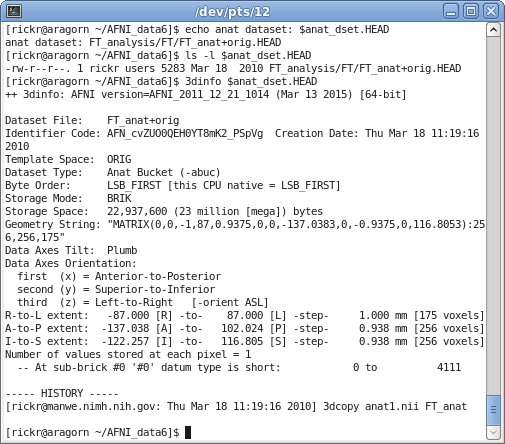

echo anat dataset: $anat_dset ls -l $anat_dset 3dinfo $anat_dset

The

echo anat datasetcommand should show ‘FT_analysis/FT/FT_anat+orig’, but the subsequent ‘ls -l’ command should fail, because there is no actual file of that name (the files end in either .HEAD or .BRIK, not just +orig). The ‘ls’ command should produce the error:ls: … No such file or directory

However ‘3dinfo $anat_dset’ works fine, because AFNI programs do not need the complete filename, just the prefix (FT_anat) and view (+orig). The output is text describing the dataset (location in space, resolution, command history, etc).

Then …

commands (type these in the terminal window):

echo anat dataset: $anat_dset.HEAD ls -l $anat_dset.HEAD 3dinfo $anat_dset.HEAD

Note

Since ‘.’ is not a valid variable name character, .HEAD is simply appended to the value of the $anat_dset variable. We do not need to use {}, as in

${anat_dset}.HEAD, though it would not hurt to do so.Next, an echo command merely appends .HEAD, which we expect is the actual name of a file (though echo does not care). The subsequent ‘ls’ command should now succeed, since $anat_dset.HEAD should actually exist. The command should just output a long listing of that particular .HEAD file.

Finally, 3dinfo is repeated using the complete filename. The command works correctly, just as before (without the .HEAD).

Note

Shell variables must start with a letter, and consist of only letters, digits and underscores.

When the shell sees ‘$’, followed by some characters, the shell will interpret the variable name as the longest sequence of valid (for a variable) characters.

Curly brackets ‘{}’ can be used to separate a variable name from adjacent text, which would otherwise look like a longer variable name.

AFNI programs can access datasets without the extension in the input dataset name. A trailing ‘.’, ‘.HEAD’, ‘.BRIK’ or ‘.BRIK.gz’ are all optional. The trailing suffix is required for NIFTI datasets, as in

data.nii, for example.Unix programs need complete file names.